[ad_1]

Bristol, United Kingdom – Malik Al Nasir’s research into a slave trading family for his doctorate was not only an academic project – it was deeply personal.

The author and poet, who is of mixed heritage, discovered that his ancestors were not only among the enslaved people the Sandbach Tinne dynasty profited from but also the traders themselves.

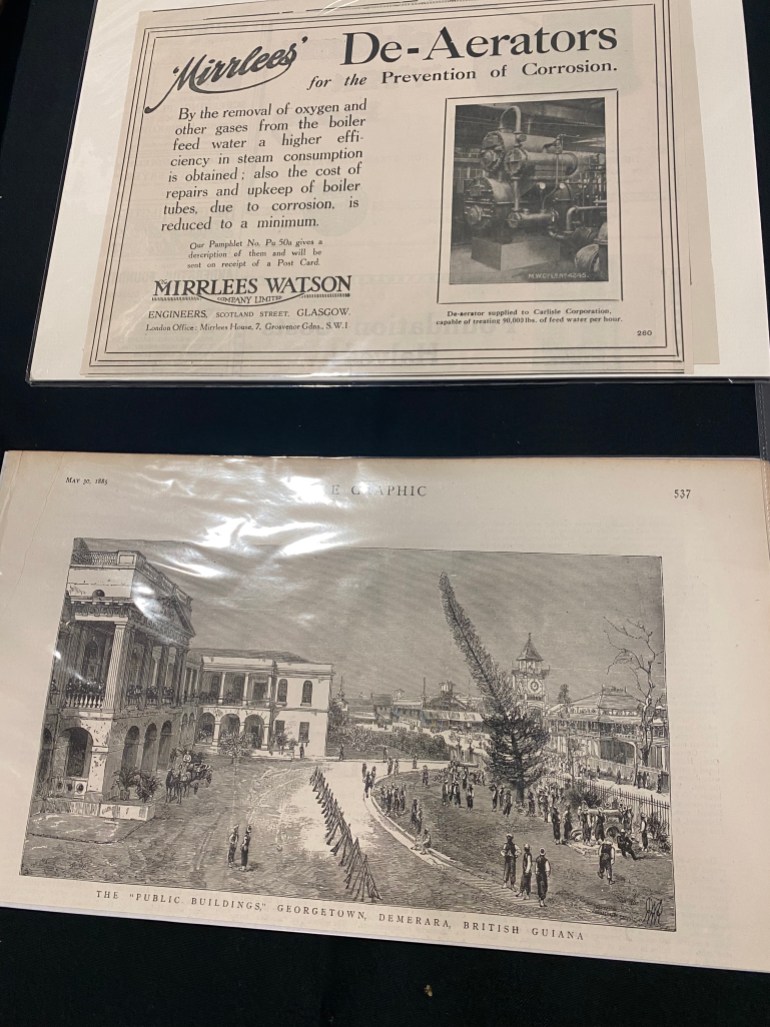

Sandbach Tinne & Co monopolised much of the Demerara sugar trade in the 19th century. Its influence and impact stretched far across the British Empire, and in the UK, the family’s wealth and legacy is visibly seen today in institutions, businesses and legacies in British cities including Liverpool, Manchester, and Bristol.

The company stopped trading only in 1975.

Al Nasir’s award-winning PhD work at the University of Cambridge uncovered missing parts of his history connected with his father’s birthplace in Demerara in today’s Guyana.

“It was important to me because I had to know who I was and how their barbaric trade of enslaved Africans shaped my life,” he told Al Jazeera. “[They] also shaped the lives of many others across the Caribbean and in the UK, in the Americas and also in Africa. So I found this work to be very essential but difficult.”

Over 20 years, Al Nasir has built an archive of photographs and ephemera relating to Sandbach Tinne. He has also gained the support of institutions, including the University of Bristol, to dig further into the family.

In this southwestern English city in June 2020, Black Lives Matter protesters, angered by the police killing of George Floyd in the United States, toppled a statue of slave trader and philanthropist Edward Colston and threw it into Bristol Harbour.

It was a scene that would be replayed across the world’s media. At the time, tensions over the legacy of slavery and the roots of racism were raging globally, and the symbolic drowning of a slave trader kickstarted a national conversation about reparations.

“There are people who’ve been fighting for reparations since the time of slavery,” said Al Nasir, who is writing a book tracing his ancestors back through slavery and colonialism, focussed on Sandbach Tinne.

The fight gained momentum again after the murder of Floyd, he said.

“We have to seize this moment and try and do what we can to keep the spectre of reparations alive and maintain that momentum.”

Al Nasir wants to establish a centre for colonial research and develop doctoral training partnerships for Black British researchers and Black Caribbean academics. With the Sandbach Tinne project, he hopes to create a multi-institutional network to further research and exhibit material related to the family. He sees work like his as a tool to enable descendants to delve into their histories and tell stories from their perspectives.

It’s one facet of a rich history of calls for reparations and reparative justice in Britain. Led by descendants of enslaved people and diaspora groups, grassroots campaigners have long called for meaningful reparations as a way to address the historical and ongoing trauma stemming from Britain’s role in transatlantic chattel slavery.

From grassroots to mainstream

In April, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak refused to apologise for the country’s role in the trade of enslaved people and ruled out reparations.

Research published by the University of the West Indies two months later estimated that the UK alone is required to pay $24 trillion as reparations for its involvement in transatlantic slavery in 14 countries.

Pressure built up further in August when a leading United Nations judge said the UK could no longer continue to ignore calls for reparations and urged the country to change its position.

Some descendants of enslavers have apologised for their ancestors, and for the first time, King Charles publicly stated his support for research into the British monarchy’s historical links with enslavement after an investigation by The Guardian newspaper into its own connections with slavery.

Elsewhere in Europe, there are some moves towards recognising grim histories.

Over the past year in the Netherlands, both the prime minister and the king have apologised for slavery. In April, Portugal’s president suggested his country should do the same.

“It’s good now that the idea of reparations is not a fringe issue any more,” said Cleo Lake, a creative artist and former lord mayor of Bristol.

In her earlier role as a Green Party councillor, Lake brought forward a motion for an “atonement and reparations” plan for Bristol’s role in the transatlantic trade in enslaved people, which was passed in 2021.

Two London councils, Islington and Lambeth, passed similar motions the previous year, calling on the British government to establish a commission to study the impact of the UK’s role in transatlantic slavery, its legacies and impact today.

But none of these calls has been heeded, signalling the resistance to the concept of reparations within the UK’s political establishment.

Al Nasir has said he has also been hit with backlash.

“There’s a lot of defensiveness to this type of research and a lot of misunderstandings around it,” said Cassandra Gooptar, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Wilberforce Institute at the University of Hull who studies UK institutions and their links with enslavement.

Gooptar is from Trinidad and Tobago and moved to the UK in 2019.

She saw “in real time” the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement in her field through an increase in jobs and roles related to researching links with slavery, including her role with The Guardian newspaper.

She contributed to the Legacies of Enslavement project released in 2023, in which The Guardian committed more than 10 million pounds ($12.7m) over the next decade to a restorative justice programme.

Gooptar hopes that other institutions across media, heritage and education will take note and for greater connections between the UK and Caribbean communities. “There’s such a big gap between what’s going on in the UK and what’s going on in the Caribbean, and that’s something I feel so disappointed about in general,” Gooptar said.

“The communities we’re talking about, the plantations we’re talking about, the people we’re talking about – and I’m speaking as a Caribbean person – the information is not getting there. I can’t really see the impact if I’m honest,” she said, reflecting on a recent trip back home to Trinidad.

That impact is the long-term goal for some policymakers.

“Ultimately, the first thing we need is for the UK to accept some responsibility,” said Bell Ribeiro-Addy, an MP with the Labour Party and chairperson of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Afrikan Reparations (APPG). She convened the group’s first conference in October.

“There have been more conversations in the mainstream, and I’m really encouraged by the momentum that the reparations campaign internationally has built.”

She hopes to see a move towards significant policy change, including in education and school curriculums.

“We are making the progress which some people have fought decades for.”

The radical roots of reparations activism

Born in south London to a Guyanese mother and Barbadian father, Esther Stanford-Xosei has been involved in the international reparations movement for more than two decades.

As a specialist lawyer in jurisprudence, she uses her legal knowledge in her efforts.

In 2015, Stanford-Xosei co-founded the Stop the Maangamizi campaign, which derives its name from the Swahili term for the genocide and ethnocide of African people and the continuum of chattel, colonial and neocolonial enslavement.

She says the campaign lobbied Ribero-Addy for the APPG’s establishment and the October conference.

“We’re in a unique time,” Stanford-Xosei said. “The fact that reparations are becoming more embraced, recognised and supported by different sectors in society is really down to the movement and movement activists who have been out there doing public education, activism and narration.”

The first and most crucial demand is the establishment of the All-Party Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry for Truth and Reparatory Justice, she said.

“We have to have a process of truth telling and truth restoration. We assume we know the truth. We only know parts of the truth, but the history, our story, has not been told.”

Stanford-Xosei acknowledged that seeds planted by previous generations are now bearing fruit, but in her view, the current push should be seen with some scepticism.

“The success of the movement has led to non-governmental organisations and powerful institutions seeking to capture the movement as a way of preventing it from achieving its radical ends,” she said, referring to the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) Ten-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice, which calls for a formal apology, debt cancellation and investment into Caribbean countries by former colonial powers.

In November, the 55 members of the African Union and the 20 countries of CARICOM announced the establishment of a global reparations fund based in Africa.

“We have our elites speaking on behalf of our communities,” Stanford-Xosei said. “To just redistribute resources to colonial states is not repair. Resources meant for the wider masses get appropriated and redirected, and that is what we’re seeing with the CARICOM Ten-Point Plan.”

Stanford-Xosei said surface-level changes are being described as reparations while systemic and structural changes are vitally needed.

“There’s a form of reparations-washing. Calling equity, diversity and inclusion ‘reparations’ won’t fundamentally challenge the structural injustices and power imbalances.”

That’s an observation that Lake also makes.

Lake was the lord mayor of Bristol from 2018 to 2019 and charts her involvement in reparations campaigning back to her childhood when she attended Colston’s Girls’ School. Because it bore the name of the slave trader, its name was changed to Montpelier High School in 2020.

In 2021, Lake worked on Project TRUTH, which was commissioned by the Bristol City Council and the Bristol Legacy Steering Group and detailed how the city should memorialise its involvement in the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans.

“Although we’ve had a couple of moments of energy, I do feel that the radicalness of the African heritage community isn’t what it was,” Lake said. “People’s understanding of decolonisation and some of these matters, it’s about inclusion and replicating the oppressiveness. But that isn’t what this campaign is about; it’s about creating something new and trying to restore ourselves.”

Stanford-Xosei’s and Lake’s perspectives demonstrate some of the tensions within the reparations movement as it becomes more mainstream. They are concerned that it risks losing some of its more radical roots and ambitions and that governments, rather than communities, will become recipients of financial aid.

They also consider reparations to be more holistic, for example, taking the form of education, land and housing rights and repatriation of cultural artefacts.

“There are so many different movements, so many different campaigns and different voices on reparations, and they don’t all agree. But what we aim to do is come to a consensus where we do agree,” Ribeiro-Addy said at the October conference, which resulted in a statement calling for the establishment of a truth, reparations and justice commission.

“Reparations is as much about the process as it is about the outcome,” Stanford-Xosei said. “For communities in Britain, our vision of a repaired world is totally different to what’s coming out of the African Union or CARICOM.”

Moving towards change

In 2016, film director John Dower discovered through University College London’s Legacies of British Slavery database that his family, the Trevelyans, had owned six plantations in Grenada at the time of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

More than 1,000 people were registered as the family’s property and after the act’s passage, the family were given as much as 29,000 pounds ($37,000) in “compensation”.

The British government gave a total of 20 million pounds ($25m) to enslaving families from 1835 to 1843.

“My family was no longer the same family I thought it was, and my life literally changed at that moment,” Dower told Al Jazeera.

In February, Dower publicly apologised for his family’s role in enslavement in Grenada.

Two months later, he co-founded Heirs of Slavery, a group intended to bring together descendants of those who made significant wealth from or helped organise transatlantic chattel slavery to listen to the perspectives of grassroots and reparations campaigns.

Dower said that since Heirs of Slavery formed, about 200 people have approached the group. He estimated that as many as 70 percent of them are descended from enslavers or those involved in enslavement whether that was as plantation owners, shipping merchants or other beneficiaries.

He hopes more people will join the initiative.

“I think, once we start getting a groundswell of people who are willing to accept what their ancestors did and not view it as a terrible threat, then hopefully, we can start to make some kind of significant change.”

Lake too speaks of a critical mass of people coming together to enact change.

“I think it will take a massive groundswell of people of African heritage coming together from various different backgrounds and standing alongside each other to represent one group,” she said.

Those involved in reparative justice accept that there are bound to be divergent views but agree on one thing – that progress is a must and the Black Lives Matter movement acted as a catalyst.

“Reparations is a really liberatory vision,” Stanford-Xosei said. “Reparations is a world-remaking project. As part of remaking the world, we have to remake ourselves.”

[ad_2]

Source link